Car accidents create a lasting impact that extends far beyond the day of the collision. Especially when that pain lingers beyond an expected period of time due to an undiagnosed nerve injury.

When looking for answers to questions about chronic pain after a car accident, it’s natural to head straight to your favorite search engine. But most results populate with options for settlement lawyers, injury lawyers and chiropractic clinics offering assessments—not medical explanations for the source of your pain.

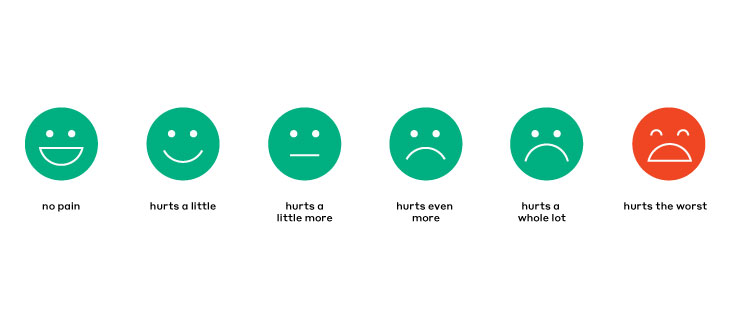

It’s important to understand the injuries sustained and their related symptoms. Meet with your doctor to discuss how you’re feeling after your accident. During your appointment, don’t hold back about your symptoms. Being thorough about what you’re experiencing isn’t complaining, it’s proactive. Be sure to ask about the potential for nerve damage.

sources of nerve damage from a car accident

When a car accident occurs, there are many common injuries and pain that can impact those involved, including nerve damage. But because there isn’t always visible trauma with nerve damage—skin doesn’t have to break for the damage to happen—it’s not always obvious upon first examination.

When pain lingers after proper and immediate medical attention, nerve damage might be the culprit. Nerve damage occurs when nerves are cut, compressed or stretched—all of which can happen as the result of a motor vehicle accident.

Chronic pain and nerve damage may also occur due to a neuroma. A neuroma is a tangled mass of nerve and scar tissue that may form when nerve damage, either from the injury itself or during a corrective surgical procedure, goes unrecognized or isn’t properly repaired.

injuries that can lead to nerve damage

Broken bones and fractures

Nerves travel in close proximity to bones and joints. As a result, broken bones and fractures can often lead to nerve injuries. Sometimes nerves are stretched, cut, bruised or crushed when a bone is fractured, but it may not be recognized immediately.

Lacerations

Abrasions and lacerations are some of the most prevalent injuries sustained during car accidents. Depending on the severity of the laceration, different layers of the skin and muscle are at risk of injury, but a deep cut from broken glass can also lead to a nerve injury. There are many opportunities for lacerations during a car accident. Even if you visited the ER after your accident, it’s possible a nerve injury wasn’t immediately recognized. As many as 91% of nerve injuries are missed in the ER, and these injuries may lead to chronic pain even after the original wound has healed.

signs and symptoms of nerve damage

Peripheral nerve damage typically presents itself in a few ways.

numbness or tingling

A loss of sensation in the extremities or a constant feeling of “pins and needles” could point to nerve damage. This damage can be caused by pinching of the nerve that occurred upon impact and can lead to chronic pain after an accident.

shooting or radiating pain

Irregular, persistent bouts of pain that originate from a particular location could be a sign that nerves were damaged in the accident.

headaches

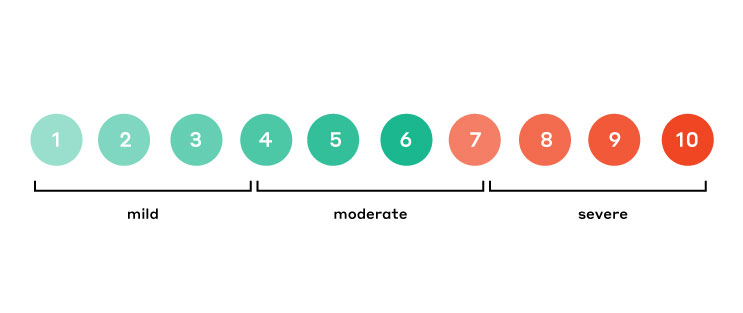

It’s important to pay close attention to the location and severity of headache pain after a car accident. While it could just be stress-related, it might also be the result of a compressed nerve.

If your injuries do not heal with time or after physical therapy (as most acute injuries should), it might be time to consider that the damage was far greater than simple strains or bruises.

nerve repair is possible

In the past, surgical options for repairing nerves were limited and had variable rates of success in alleviating nerve pain or restoring function. Procedures that only cut the nerve but do not repair it, leave the nerve with the potential to form a future painful neuroma and don’t give you the chance to regain sensation or function.

Thanks to advances in nerve surgery, living with nerve damage and the associated pain isn’t your only option. Many types of peripheral nerve injuries, especially injuries that can be linked to a previous surgery or injury, can likely be treated surgically.

Depending on the specific nerve damage, a nerve surgeon can repair the nerve by either reconnecting the nerve with a nerve graft to allow restoration of normal signals to the brain; isolating the nerve end with a nerve cap to reduce the potential for neuroma formation; or occasionally rerouting the nerves.

If you think you are experiencing chronic pain due to nerve damage from a car accident, you may be a candidate for nerve repair surgery.