Nerve pain is unrelenting and all too often, unbearable. When the time comes to take care of the problem at its source, who do you call?

just who is a nerve surgeon?

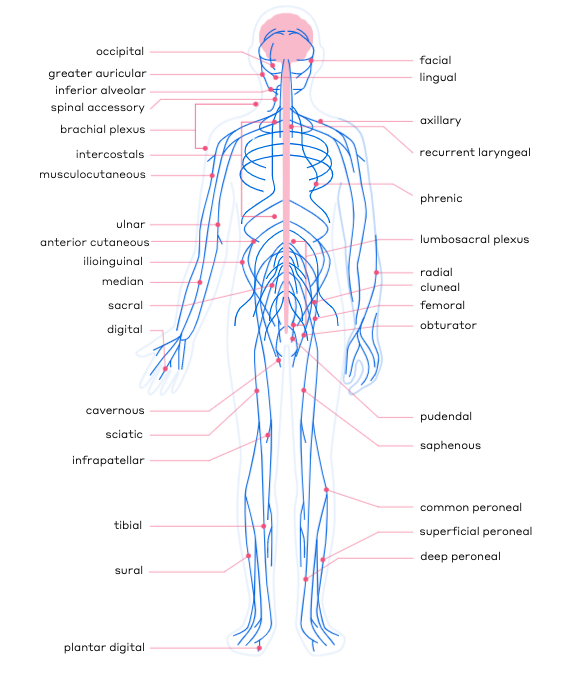

Simply put, nerve surgeons specialize in the surgical repair of peripheral nerves, but since nerves run throughout every inch of our bodies, there is not one specific type of surgeon or title that aligns precisely with the specialty of nerve surgery. Instead, there are several types of doctors who specialize in nerve repair. These doctors undergo extensive microsurgical training to become experts in their field.

Simply put, nerve surgeons specialize in the surgical repair of peripheral nerves, but since nerves run throughout every inch of our bodies, there is not one specific type of surgeon or title that aligns precisely with the specialty of nerve surgery. Instead, there are several types of doctors who specialize in nerve repair. These doctors undergo extensive microsurgical training to become experts in their field.

While injured or damaged nerves can certainly cause a large amount of pain, they are very tiny structures and repairing them can require the use of magnification and specialized knowledge of nerve repair techniques.

The most common physicians who perform nerve surgery are:

- plastic reconstructive surgeons

- orthopedic hand surgeons

Additionally, there a select number of other specialists have undergone training for microsurgical nerve repair, such as:

- neurosurgeons

- oral maxillofacial surgeons

- doctors of podiatric medicine (DPMs)

Let’s dive in and learn a little bit more about these specialists, and how each—while not necessarily called a “nerve surgeon”—is qualified to treat nerve damage that may be the cause of chronic pain.

plastic reconstructive surgeons

You may be thinking, “Why would I go to a plastic surgeon for help with nerve pain?”

It’s a common misconception that plastic surgeons only perform cosmetic surgery. In fact, plastic surgery is generally broken down into two areas of concentration: cosmetic and reconstructive.

Cosmetic or aesthetic plastic surgeons often focus on breast augmentation, facelifts, rhinoplasty, etc.

Reconstructive plastic surgeons typically focus on more complex cases that may involve, for example, helping to save a patient’s limb after a traumatic injury or helping to rebuild an area of the face that has been badly damaged.

The word “reconstructive” means “to rebuild after something has been damaged or destroyed,” and these surgeons are trained to reconnect ligaments, muscle tissue and blood vessels to repair damage to a patient’s body. In addition, they often reconstruct and repair nerves.

With extensive microsurgical training, nerve repair is something that reconstructive plastic surgeons perform regularly, especially with patients facing chronic pain caused by a nerve injury.

orthopedic hand surgeons

You may think of an orthopedic surgeon as someone who you see when you break your arm or injure your knee, or when you need a hip replacement. That’s a fair assumption. Orthopedic surgeons specialize in treating your musculoskeletal system—your bones, joints, tendons, muscles and ligaments. They are experts at understanding where and how your body fits together.

And they can also specialize in nerve repair.

As doctors who specialize in muscles and nerves, many orthopedic hand surgeons have made nerve repair a primary focus. But don’t let the term “hand surgeon” fool you. The most common location for a nerve injury is the hand, and these surgeons have received extensive training on the intricacies of nerve repair, not just in the hand, but throughout the rest of the body.

neurosurgeons

While the term “neuro” and “nerve” may seem to go hand in hand, many neurosurgeons are mostly focused on the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord), rather than the peripheral nervous system (the nerves running all through the body). The function of each is quite different and they serve different purposes.

There are some neurosurgeons who also specialize in working on the peripheral nervous system who are trained to deal with nerves throughout the body.

oral maxillofacial or Ear Nose and Throat (ENT) surgeons

Oral maxillofacial and ENT surgeons focus on the hard and soft tissues in the head, neck, face and jaw. These dental experts can help treat cleft lips, head trauma injuries, and perform reconstructive surgery on head and neck cancer patients.

Some oral maxillofacial and ENT surgeons are also skilled in performing nerve repair on injuries sustained to nerves in the face or jaw. For example, these specialists often work on nerve injuries that can sometimes occur during wisdom tooth extractions or other dental procedures.

foot and ankle surgeons, or doctors of podiatric medicine (DPMs)

It is important to recognize that most DPMs focus only on the tendons, bones and ligaments of the foot and ankle, and do not often specialize in nerve repair.

However, there are a small number of DPMs who have undergone microsurgical training to be able to perform nerve surgery in the feet and lower legs.

is there a qualified nerve specialist near me?

Take our quiz to see if you qualify as a candidate for surgical nerve repair. And then use our Find a Surgeon tool to see who might be a good fit for your needs and where they are located.

Not all plastic surgeons, orthopedic surgeons or neurosurgeons work with peripheral nerves. However, every doctor suggested through our Find a Surgeon tool—whether ortho, plastic or neuro—has taken specific interest in and developed a passion for helping patients with peripheral nerve injuries.